The government headed by Giorgia Meloni has focused heavily on migrant centers in Albania to reduce the pressure, including the psychological pressure of landings in Italy, to disincentivize those who head to Italian shores already knowing that they do not qualify for international protection, and to avoid the flood of irregular migrants who easily escape from the overcrowded and poorly supervised detention centers for returns (CPRs) in Italy and enter illegally

But the Italian Prime Minister moved two years ahead of the entry into force of the new European Regulation (2024/1348) repealing the EU Directive 2013/32 currently in force.

The delicate point concerns the definition of safe country of origin. In fact ,according to the agreements between Italy and Albania, only migrants whose country of origin can be defined as safe and who can therefore undergo the accelerated border procedure can be detained in the Shëngijn and Gjadër centers.

The Directive still in force, which will be replaced by the Regulation approved in the spring of 2024 but will not be applied until June 2026, stipulates that for a country to be considered safe it must be so throughout its territory and without distinction for certain categories of people.

Applying this rule, the European Court of Justice on Oct. 4, while examining a case concerning Moldova, whose Transnistria Region is not considered a safe zone due to Russian interference, ruled that EU law does not currently allow member states to designate as a safe country "only part of the territory of the third country concerned."

From that moment on, the Italian magistrates dealing with these problems conformed to the guidance expressed by the Luxembourg Court and ordered the transfer to Italy of the , very few , migrants who had been taken to Albania ,because their countries of origin, Egypt and Bangladesh, could not be considered entirely safe.

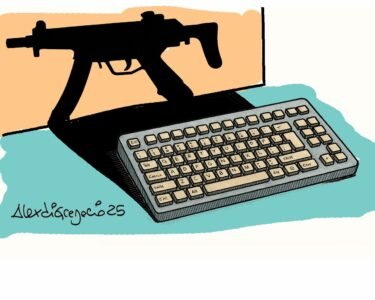

The government unfairly lashed out at magistrates who only applied the regulations. It tried to overcome the obstacle in two ways :it drew up by a primary regulatory act(a decree-law) a list of countries that Rome considers safe and it took away the power to decide on these issues from the special sections of the Courts (which had spoken out against the transfer of Egyptian and Bengali migrants to Albania) transferring it to the Courts of Appeals. But the Courts of Appeals in Italy are burdened with work, have few magistrates at their disposal and have never dealt with these issues. Therefore, some of these Courts have asked the very magistrates, whose jurisdiction the government has taken away, to work with them......

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court has recognized the government's right to define which countries are safe and which are not. The Court ruled regarding a case when the list of safe countries was contained in a legislative decree transposing the European Directive. But the principles that the Supreme Court established also apply to the list contained in a law today.

Safe country qualification is not a political act over which the government can claim total autonomy. The list is a technical act characterized by discretion and must comply with the requirements of Directive 32/2013 and other Italian regulations. .Since a constitutional right ( the right to 'asylum and protection ) is at stake, the final word must rest with the magistrate In the case examined by the Supreme Court, the judge can legitimately disapply the legislative decree, without cancelling it. Now that there is the list established by law, the judge can object to the correctness of the qualification of a country as safe, taking into account elements that are evident at the time when the judgment takes place.The judge can also assess whether, in the case of the individual person he is examining, there are valid reasons for considering the migrant to be the object of a threat.In this case there is no need even to disapply anything:according to current European norms, the judge denies the accelerated border procedure and orders the ordinary one.

This is a balanced decision of the Supreme Court that the government has exaggeratedly considered favorable to its line. But it is not. If the list of safe countries were contained in the current European Directive, the magistrate's discretion would not be allowed. But this is not the case.

What will happen now? Giorgia Meloni is right that her government's idea of creating centers abroad for migrants is being watched with interest by other countries. But as long as the current Directive is in force, the Italian government can never be sure that its definition of a safe country cannot be disapplied in specific cases by magistrates.

The only possible solution would be to bring forward the entry into force of the European Regulation. It provides in Article 61 that: "The designation of a third country as a safe country of origin at both Union and national level may be made with exceptions for certain parts of its territory or clearly identifiable categories of persons." In addition, the Regulation provides for the accelerated examination (and refoulement) procedure if they come from a safe country of origin or a country with an acceptance rate for applications for international protection of less than 20%

In short, the Italian government has only to ask Ursula von der Leyen to propose bringing forward the entry into force of the International Protection Regulation or at least to allow countries that want it to apply it right away and without waiting until June 2026.