One of the most representative works of the father of dialect theater, it interrogates contemporary audiences about identity. The play, in the post-Basaglia law adaptation by Leo Muscato, offers an ironic and merciless reading of all contemporary foibles, unmasked precisely by the protagonist's deception. Tour dates

By Rosalba Panzieri

“Il medico dei pazzi,” a celebrated play by Eduardo Scarpetta, has returned to the Italian stage, marking the centenary of its author's death. The father of modern dialect theater, Scarpetta was a leading actor and author of Neapolitan theater. Eduardo, Titina and Peppino De Filippo, born of his relationship with Luisa De Filippo, are Scarpetta's other great gift to international theater.

To celebrate the author, Rome's Teatro Quirino has chosen to bring one of his most representative works to the stage, which will run through several Italian theaters, until Feb. 15.

“Il medico dei pazzi” lightly and intelligently stages the fine line between normality and madness, restoring all the flavor of great Neapolitan theater. A masterpiece also made famous by the film version starring Totò, the comedy revolves around the popular mask of Sciosciammocca, created by Eduardo Scarpetta and becoming a symbol of timeless humor.

The plot

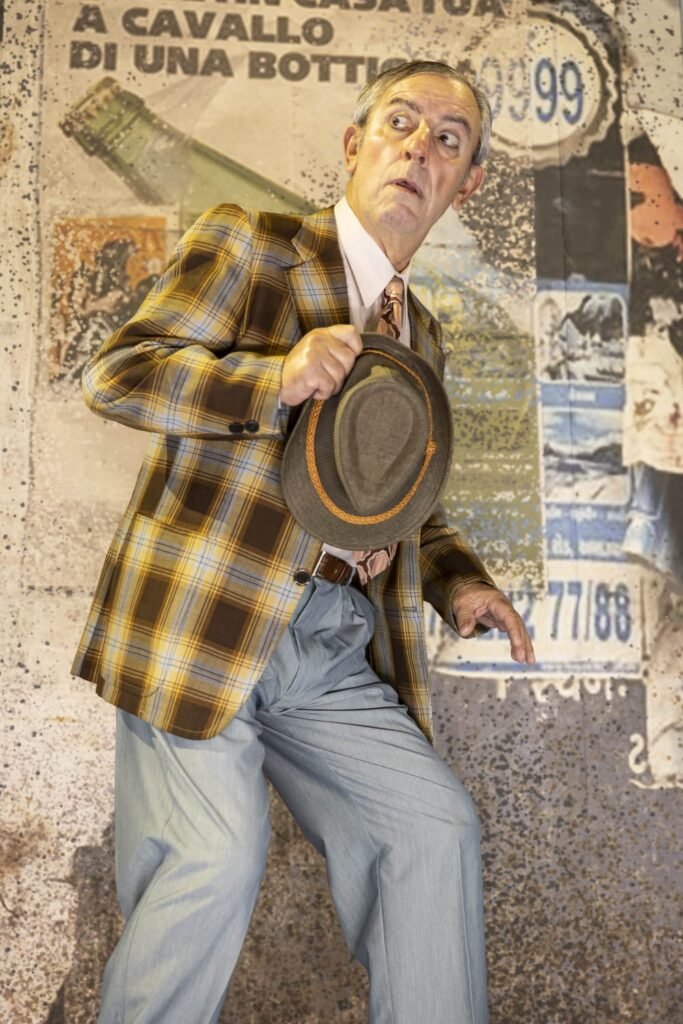

Don Felice Sciosciammocca, a naïve and well-to-do provincial, arrives in Naples with his wife to visit his nephew Ciccillo, whom he has kept in his studies and who now tells him he has become an accomplished psychiatrist, director of a prestigious clinic for the mentally ill. Caught off guard by his uncle's unexpected arrival, Ciccillo improvises a colossal lie: the Pensione Stella, where he lives as a runaway, instantly becomes a respectable nursing home. Convinced that he is really in a mental institution, Don Felice mistakes the eccentric and unsuspecting guests of the boarding house for patients suffering from the most curious foibles, giving rise to a maelstrom of misunderstandings, misinterpretations and paradoxical situations. A whole series of comic situations, which have entered the collective memory of Neapolitan theater, thus come to life.

Between a bumptious major, a penniless and somewhat kleptomaniac musician, an amateur actor obsessed with Othello, and an intrusive mother looking for a husband for her daughter, the Stella Boarding House turns into a veritable ’circus of horrors“ in her eyes. With each encounter his bewilderment grows, to the point where it is Sciosciammocca himself who seems the craziest of them all, swept up in a game of mirrors that questions his own identity.

From nineteenth-century reality to post-Basaglia reality.

In Scarpetta's original version, “Il medico dei pazzi” is set in late 19th-century Naples, a working-class and middle-class city traversed by social transformations, new fashions and new fears. The insane asylum is a mysterious and feared place, and comedy arises from the misunderstanding: mistaking a boarding house for a mental hospital.

It is a society that lives by appearances, rigid roles, and bourgeois naiveté that Scarpetta unmasks with farce.

Instead, Leo Muscato's direction shifts the story between the late 1970s and early 1980s, in the midst of the cultural revolution of the Basaglia Law, which abolished asylums and introduced new forms of treatment, viewed with suspicion, especially by a naive provincial like Don Felice.

“The closure of asylums,” Muscato explains, "generated an era of distrust and bewilderment. It was the perfect time to shake Don Felice's certainties.".

Arriving in Naples, in fact, Sciosciammocca finds himself in a city in turmoil, contradictory, colorful, where he can no longer distinguish who is sane and who is not. His identity cracks, to the point of the most radical question: what if he is the real madman?

This temporal shift allows the director to play with an iconic aesthetic of sideburns, oversized glasses, bell-bottoms, and a timeless soundtrack. But beyond the fun, a deeper reflection on identity emerges.

If we can all be mistaken for someone else, who are we really?

A direction that can speak to the present

This is where the new direction meets the essence of Scarpetta.

In the 19th century, farce exposed bourgeois clumsiness.

In the 1970s, it unmasks the ever-living fragility of a country that does not yet know how to live with freedom, with care, with its own identity. But it is in the spectators of that the scenic matter finds breath and space for reflection, forcing us to question the concept of normality and madness. What if our society is actually normalizing endless manias?

“Scarpetta,” Muscato points out, "was laughing at his contemporaries. I try to make us laugh at ourselves, because our confusion is not so different from theirs.".

The play flows brilliantly, highlighting the skill of the actors, who know how to keep an excellent narrative balance. Some interpretative exasperations do not appear out of place here, but stand as an unapologetic mirror of the contemporary world. What endures, however, between normality and madness, is a certain poetic tension.

“And at the finale,” the director concludes, "as the audience laughs, Don Felice, his heart swollen with disappointment, realizes that he has been gulled like a poor fool: his beloved nephew, the one for whom he has sacrificed years and money, has cheated him with the shamelessness of someone who cheats at cards with a blind man. He smiles bitterly, hugging himself in his misplaced provincial jacket. Perhaps he really is the maddest of them all, for, in spite of everything, he cannot deny anyone the luxury of a poetic happy ending." And it is precisely in this ending that Don Felice's defeat restores to him a nobility that makes one fall in love with the character.

Tour dates:

Jan. 27 in Brindisi, Jan. 28 to Feb. 1 in Bari, Feb. 8 in Novi Ligure, Feb. 11 in Pinerolo, Feb. 14 to 15 in Civitavecchia.